The rapid shuttering of business doors across the nation during the initial coronavirus outbreak left many advertisers scrambling to adjust their marketing strategies. Aside from the fear of lost revenue, companies initially planning to run Spring campaigns stood the risk of coming across as tone-deaf if they didn’t pivot during the pandemic.

To adjust to a radically changing consumer landscape, brands quickly created ‘coronavirus campaigns’. These campaigns acknowledged in some capacity the drastic lifestyle changes that many Americans were experiencing. Copy that likely expected to evoke the whimsy of “spring”, instead used words like “quarantine”, “social distancing”, and “essential” to draw consumers to products.

Of course, this attempt by businesses to push product during a pandemic did not always hit the mark, as noted by this Twitter user:

Yet, brands who leaned on one of three major concepts (escapism, solution, community) to create a coronavirus campaign were able to somewhat successfully position their products or services amid a global pandemic.

ESCAPISM

An escapism-oriented ad campaign acknowledged the general terribleness of the situation but sought to offer some type of metaphorical escape. For “non-essential” businesses, this type of campaign attempted to lure consumers who were looking to indulge in some capacity—be it socially-distanced drinking, self-care, or a literary reprieve.

The Stay the F*ck Inside app is a drinking game that encouraged social distancing measures while also offering a platform on which users could still engage in “social drinking”, even from afar. Bambu Earth leaned on the blended concepts of skincare as self-care and suggested consumers use quarantine as an escape to “detox” their skin.

Finally, Book of the Month club offered a literary escape with a COVID-inspired code (“take care”) for a discount on their monthly subscription.

SOLUTION

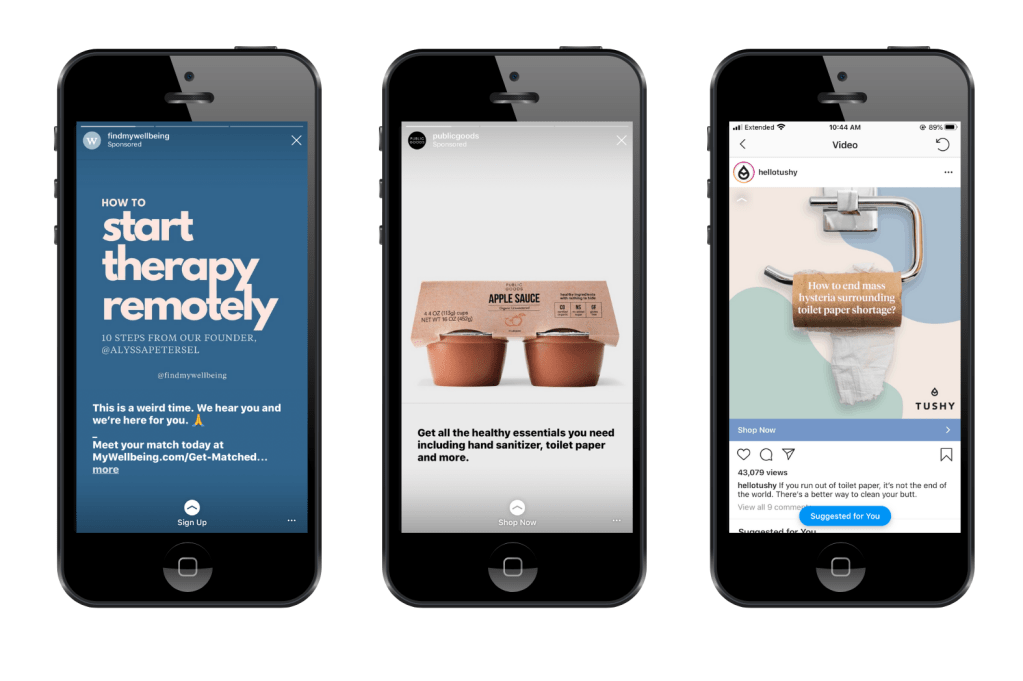

By and large, products that committed to a solution-oriented ad campaign were already well-positioned to do so. As many Americans quarantined inside their homes, they naturally sought online and/or delivery alternatives to replace normally in-person or “outside” essential services.

For instance, because of the pandemic’s toll on mental health and the dangers of in-person food shopping, online therapy and grocery delivery services became increasingly popular. Find My Wellbeing promoted its online services by offering helpful tips on how to start remote therapy. Public Goods used several common COVID-19 “trigger words”—essential, toilet paper, hand sanitizer—to engage consumers as an online delivery service that could provide them with in-high-demand supplies.

The other ad included in this category—Hello Tushy—was an interesting case of a traditionally “non-essential” item in American culture (a bidet) attempting to position its product as a solution-oriented approach in response to the shortage of toilet paper.

COMMUNITY

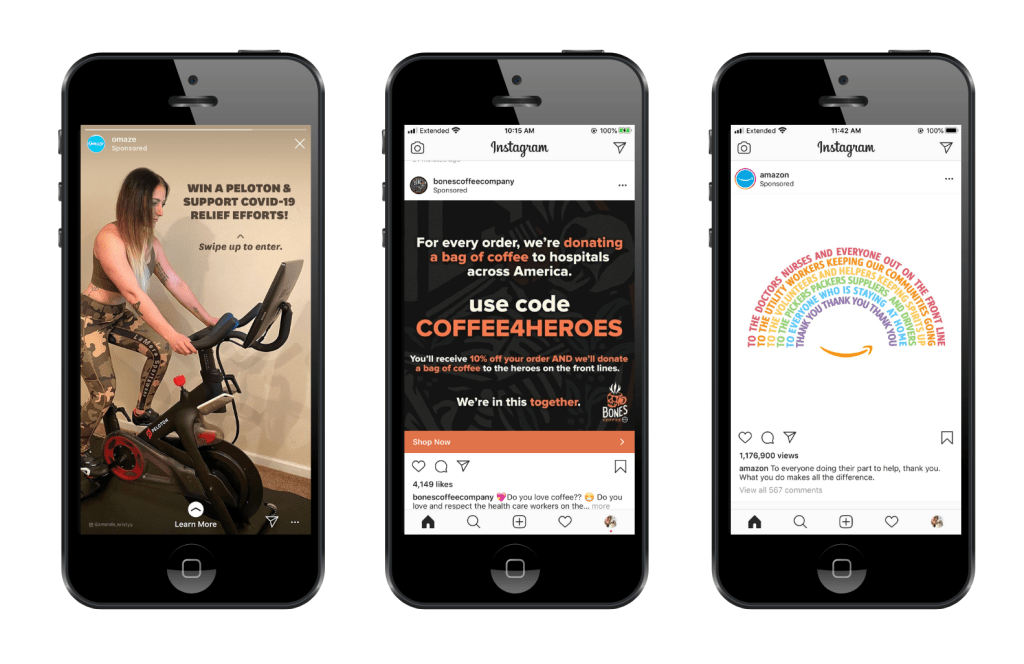

Community-oriented ads were comprised of both non-essential and essential services attempting to showcase their businesses as an active, philanthropic member of ‘community’. Typically, these ads promoted, in addition to their product, a company’s efforts to support COVID-related causes. These messages attempted to persuade consumers to buy because they would also, in theory, be supporting a good cause.

For example, the Amaze ad suggested that consumers who paid-to-enter a Peloton bike raffle would also be supporting COVID-19 relief efforts. Bones Coffee pledged to donate one bag of coffee to medical workers for every order purchased using a special code.

And, finally, Amazon. Amazon was (is) a unique case because its service could employ both escapism and solution-oriented ad campaigns. However, they chose a community campaign that—in notable contrast to others—did not offer a donation to relief efforts, just gratitude for essential workers. (Further ironic now that Amazon is under fire for their treatment of their own essential workers during the crisis.)

In large part, how companies or brands developed their ‘coronavirus campaigns’ and positioned their products during the pandemic was based on the essentialness of their service and how they were already poised to serve consumers pre-COVID-19.

Non-essential services (Stay the F*ck Inside, Bambu Earth, Book of the Month) created campaigns that positioned themselves as a method of escape from current circumstances through socially-distanced drinking, skincare as a method of self-care, and reading.

Other companies sought to position their businesses as a solution to consumers looking for remote and delivery options for essential items or services (Find My Wellbeing, Public Goods, Hello Tushy).

Lastly, some businesses leaned on the concept of “community” to embody their brands with philanthropic promotion—by donations to relief efforts or thanking essential workers (Amaze, Bones Coffee, Amazon).

So, where are ads headed now, especially with quarantine fatigue stirring desire to shirk lockdown orders? Advertisers finely attuned to swiftly changing consumer attitudes are shifting their campaigns from addressing the current situation to providing consumers with what they really want—a brighter, more hopeful concept of “future”.